As a metaphor, “rubbing salt in a wound” means to make an already-bad situation worse for someone, especially in an unnecessary or gratuitous way. One hears the phrase constantly, about everything from taxes to sports. Perhaps one reason it’s so common is that, even if most of us have never literally had a handful of Diamond Crystal rubbed into an open blister, we intuitively understand it to be painful, even unusually painful (after all, the phrase isn’t “rub sugar in a wound”). And we are intuitively right! In this episode, we’re exploring the physiology behind why exactly getting salt in a wound is so painful.

Since we’re the Curious Clinicians, we first have to ask how this phrase came to be. As far as we can tell, the phrase comes from the 19th centuryand may share a lineage with the phrases “rubbing someone’s nose in it” and “rubbing it in.” Its meaning may have resonated more back then: Historically, salt has been used an instrument of torture after flogging, and in the British navy, flogged sailors would be submerged in a barrel of seawater to complete their punishment. Salt has been used for less devious purposes though. For thousands of years, humanity has used salt as a preservative, helping prevent spoilage and infection in everything from food to Egyptian mummies. Salt was so valuable in Ancient China that it even was used as a form of currency.

In the time before dedicated antiseptics like iodine or chlorine, salt was the next-best thing. The Hippocratic corpus of the 5th and 4th century BC noted that salty sea water tended to facilitate the healing of wounds on the hands of fishermen. Several centuries later, the Greco-Roman physician Galen actually recommended applying salt to all manner of wounds of skin diseases. Those poor British sailors may actually have benefited from their salt-water plunge since the fresh wounds on their backs would be less likely to get infected.

With all that salt being used on wounds, someone must have noted how painful it was. The first reference to this we can find comes from Pliny the Elder, the Roman naturalist and polymath from the 1st century CE. In his Remedies Derived From Living Creatures, he prescribes all kinds of now-odd concoctions such as “cow-dung warmed in hot ashes” and “goats dung boiled in vinegar or wine.” For boils, he says that “beef-suet is applied with salt; but if they are attended with pain, it is melted with oil, and no salt is used.” Melted beef fat and salt may be better suited to barbecue than boils, but at least Pliny identified that some people would find salt in a wound unbearable.

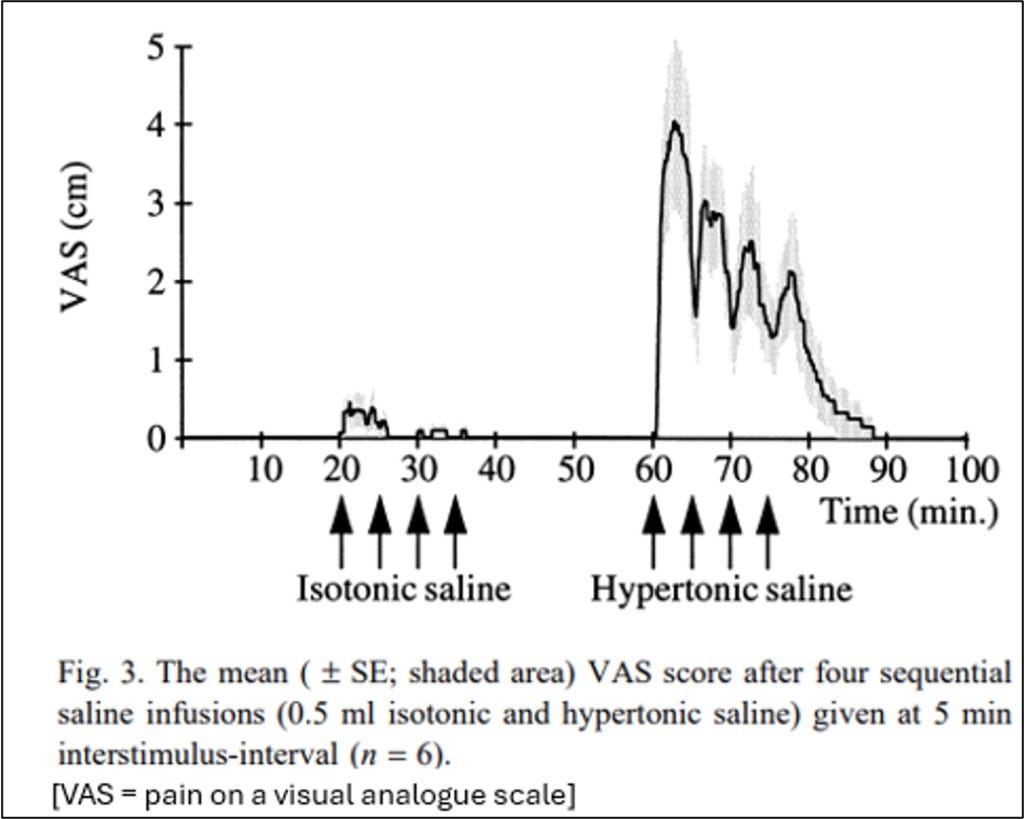

So why does salt in a wound hurt? And how bad is it really? In 1997, researchers attempted to answer the second question via an experiment in which they infused different saline concentrations into the tibialis anterior muscles of volunteers and then measured pain on a scale of 0-10, where 0 was “no pain” and 10 was “intolerable pain.” Infusing 0.9% isotonic saline led to average peak pain scores less than 1, whereas 5% hypertonic saline caused mean peak pain scores of about 4. With the hypertonic saline, the volunteers described the pain using words like “cramping” and “aching” most frequently.

Since the pain was so dependent on the salt concentration, it seems likely that the pain is coming from a local change in osmolarity. In our tissues, there are pain receptors, called transient receptor potential vanilloids, or TRPVs, which are osmosensitive. TRPV1 and TRPV4 specifically are cation channels which fire in response to increases in tissue osmolarity.

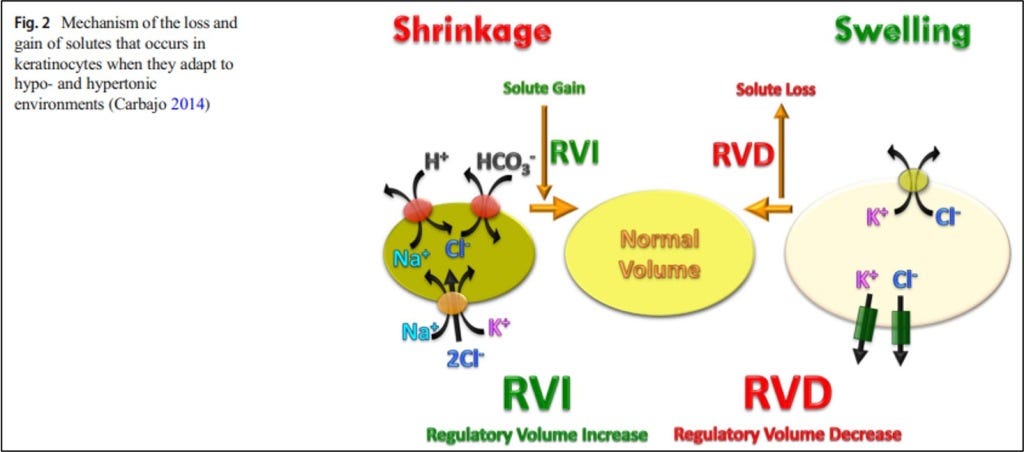

TRPVs probably aren’t the only pain receptors at play, though. In a 2011 PLoS One study they tested different degrees of hyperosmolar exposure in TRPV4 knockout mice, and they still experienced pain from a 10% saline solution. What’s causing the pain then? The most likely explanation is that the sudden increase in local osmolarity causes rapid shrinkage of cells, leading to cell stress and death, which itself is a well-known activator of pain receptors.

One unusual fact about TRPVs is that they also fire in the presence of capsaicin, the substance that makes chili peppers spicy. If you’ve ever cut your finger and then tried to sprinkle salt or handle a pepper, you’ll know that both produce a similar “burning” pain. Although many humans enjoy the sensation of eating chili peppers, capsaicin is actually a biological deterrent, meant to ward off plant predators. Fascinatingly, birds TRPVs are insensitive to capsaicin. The theory is that the plants evolved to deter creatures, like mammals, that will chew up the plant and destroy the seeds, but be hospitable to birds, who are toothless and will carry the seeds far and wide and scatter them in their droppings.

That’s not our strangest capsaicin fact though. The Trinidad Chevron Tarantula, which can grow over a foot in diameter, produces a capsaicin-like neurotoxin molecule in its venom called vanillotoxin, which also stimulates the TRPV1 pain receptor and causes a burning pain. Getting salt rubbed in a wound may be preferable to that!

Take Home Points

Pouring salt in wounds does indeed cause pain, by multiple mechanisms:

Raising wound osmolarity, which stimulates osmo-sensitive TRPV nociceptive neurons

In a fascinating twist, these are the same neurons through which capsaicin from chili peppers signals, and the venom of a certain type of tarantula from Trinidad

Another mechanism is osmotic stress leading to cellular injury and death

Link to Related Tweetorials

https://x.com/avrahamcoopermd/status/1912485105286701387?s=46&t=Jr3LdGdKRCUYiKPRh0kmag

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/show/curiousclinicians/id/36962450

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Avi Cooper and Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.comCooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G. Salt in the Wound. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. June 11th, 2025.

Image Credit: International Leadership Institute