If other animals ever praised humans, they’d probably laud our brainpower, our bipedalism, and perhaps the invention of the air fryer. They’re probably not raving about our sense of smell, but they really should. Not only is the human sense of smell far keener than we once thought, but there’s actually one odor we can detect better than almost any other creature: The smell of rain.

We love jargon on The Curious Clinicians, so let’s start with a brief vocabulary lesson. “Petrichor” is the technical term for the smell of soil moistened with water, which is what people mean when they say that they “smell rain.” The term comes from the 1964 paper “Nature of Argillaceous Odor” by Isabel Joy Bear and Dick Thomas. The word argillaceous means “clay-like” and they felt this didn’t reflect the broad range of materials which can be associated with this earthy smell, including rocks containing silica or iron oxide. They preferred “petrichor,” which literally means “essence of stone.”

There are many, many, many poems written about the smell of rain, and for good reason … it smells good! People who live along the Ganges River even make a traditional perfume called Mitti Attar by baking wet, clay-rich soil from the river banks and passing the steam through oil to capture that unmistakeable aroma. But, scientifically-speaking, what exactly IS petrichor? And why do humans like it so much?

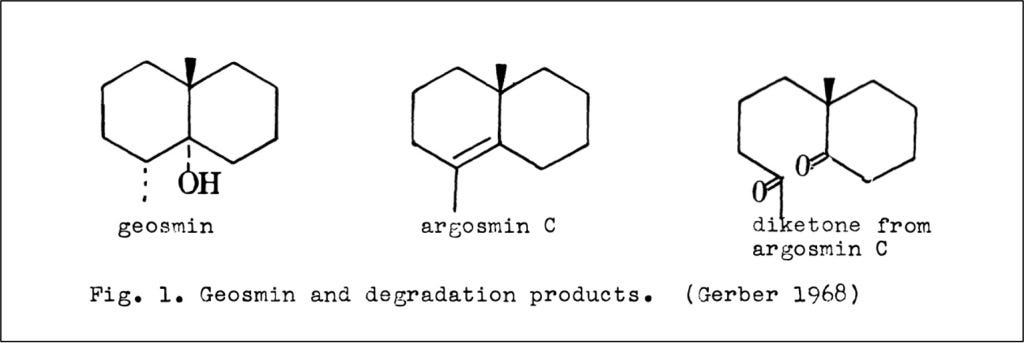

In the same year that Bear and Thomas coined the term “petrichor,” biochemist Nancy Gerber started investigating its components. It was already known that members of the phyllum Actinobacteria in fishing streams produced an earthy-smelling compound. Using chromatography, Gerber isolated several molecules, including a bicyclic alcohol she called geosmin, or “earth odor.” This was later found not only in rivers around the world, but also in beets, garden soil, a particularly earthy-smelling whiskey, corn silks, and potato-processing waste. She also found another substance, methylisoborneol (MIB), that other researchers had already isolated from algae, fish, and garden soil.

As we explored in our recent episode “The Grapes of Pseudomonas’ Wrath,” smell can sometimes be ascribed to a single compound. Petrichor is a little more complicated. In addition to geosmin and MIB, scientists have isolated many other compounds produced by Actinomyces, including several sesquiterpenoids – chemical structures similar to geosmin. These compounds each have a slightly different odor, ranging from “fruity” to “musty,” which may account for the distinct, multi-layered nature of petrichor. Mixed in with these compounds is also the smell of ozone and plant oils.

But why do humans like petrichor, especially since it’s produced by bacteria and fungi? Some have hypothesized a “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” situation. C. elegans (a roundworm) and drosophila, or fruit flies, are repelled by geosmin. Drosophila hate geosmin so much that they even have their own segregated olfactory circuit for it that can override even their attraction to vinegar. The theory, then, is that humans like the smell of water that worms and flies are less likely to be in. Not to rain on that theory’s parade (pun intended), but that logic doesn’t really hold when you consider that mosquitos love geosmin (and frankly, if you had to choose between mosquitos and fruit flies, is it really a choice?). Furthermore, why would we like geosmin if it means our water is free of roundworms but full of potentially toxic Actinobacteria, fungi, and Cyanobacteria?

One interesting finding is that at lower concentrations (around one teaspoon per 200 olympic swimming pools), humans love geosmin. At higher concentrations, we find it repellant. The same is true of MIB. Other animals use geosmin to help them navigate – land animals use it to find fresh water, and sea creatures use it to find the shore. Since geosmin signals not just water but wet soil, our ancestors may have evolved to be attracted to it since it could guide us to fertile lands, but repelled by levels that indicate polluted water.

At the beginning of this episode, we said that humans are superior smellers of geosmin. Which is true, but not the whole story. In an experimental model comparing our geosmin chemoreceptor OR11A1 to six other mammals, we did quite well, outdoing our cousins the rhesus monkey and orangutan (polar bears, who need to be able to hunt in the open sea and find their way to shore, edged us out). However, we were demolished by that most terrifying of beasts: The kangaroo rat. These diminutive rodents hop around the deserts of North America all day, looking for water hidden in plants, cacti and insects. It’s no surprise they have geosmin receptors about 100x stronger than our own.

Speaking of the desert, it’s worth talking about another dry-land dweller (and winner of the 2018 Animal House Region of Nephmadness): The camel. These beasts of burden are able to find water up to 50 miles away, which is theorized to occur due to their ability to smell geosmin and 2-MIB, as well as an incredibly efficient nasal structure. It makes sense why camels would be attuned to geosmin, since water is so scarce in the desert. But camels may also explain why geosmin production is so highly conserved amongst fungi and bacteria. It’s a classic example of symbiosis – A bacteria like Streptomyces in one oasis produce geosmin, which attracts camels, who pick up bacterial spores while drinking, only to carry them far and wide to other water sources.

As always, we can end with the question: So what does this have to do with medicine? Admittedly, we don’t use the word “geosmin” very often on rounds. But, there may be reason to. Several years ago, an internist in Turkey took 280 iron-deficient patients and asked them if they had “geosminophilia,” or an attraction to the smell of the earth. Only 34% of all patients said yes, but 72% of patients who also reported pica symptoms (meaning cravings for things like ice, dirt and coffee grounds) also had geosminophilia. Since pica can be a manifestation of iron deficiency (as many of these seemingly inedible substances contain iron), geosminophilia may be a sign of an underlying craving for mineral-rich soil.

Take Home Points

Humans have a strong ability to smell petrichor, which is the smell of rain on the ground.

This smell is composed of several compounds, including geosmin and MIB, which are produced by Actinobacteria and fungi.

At low concentrations, humans have an affinity for petrichor, which may reflect our evolutionary drive to find water and fertile soils. At high concentrations, we have an aversion to it, possibly due to avoiding high concentrations of bacteria or fungi in our drinking water.

The ability to produce geosmin is highly conserved in many bacteria and fungi, and the ability to smell it is highly conserved across mammals. This could reflect a symbiotic relationship that allows mammals to find water and Actinobacteria to reach it.

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/show/curiousclinicians/id/35893950

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

Episode written by Hannah Abrams

Show notes written by Hannah Abrams and Giancarlo Buonomo

Audio edited by Clair Morgan ofnodderly.comAbrams HR, Breu AC, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G. The Smell of Rain. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. March 27th, 2025.

Image Credit: Francois Lambert